High-Quality Surfactants for Global Markets - Trusted Manufacturer

The Unsung Heroes Inside Your Lungs: Meet the Surfactant Super-Producers

(what type of cell produces surfactant)

Breathing. We do it thousands of times a day without thinking. But behind that simple act lies an incredible biological feat. Our lungs are masterpieces of engineering, filled with millions of tiny air sacs called alveoli. These delicate structures are where the vital exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide happens. For this exchange to work smoothly, the alveoli need to stay open. They need to avoid collapsing with every breath out. This critical job depends heavily on a special substance called surfactant. So, what type of cell actually produces this life-saving surfactant? Let’s meet the cellular heroes: the Type II Alveolar Cells.

1. What is Surfactant?

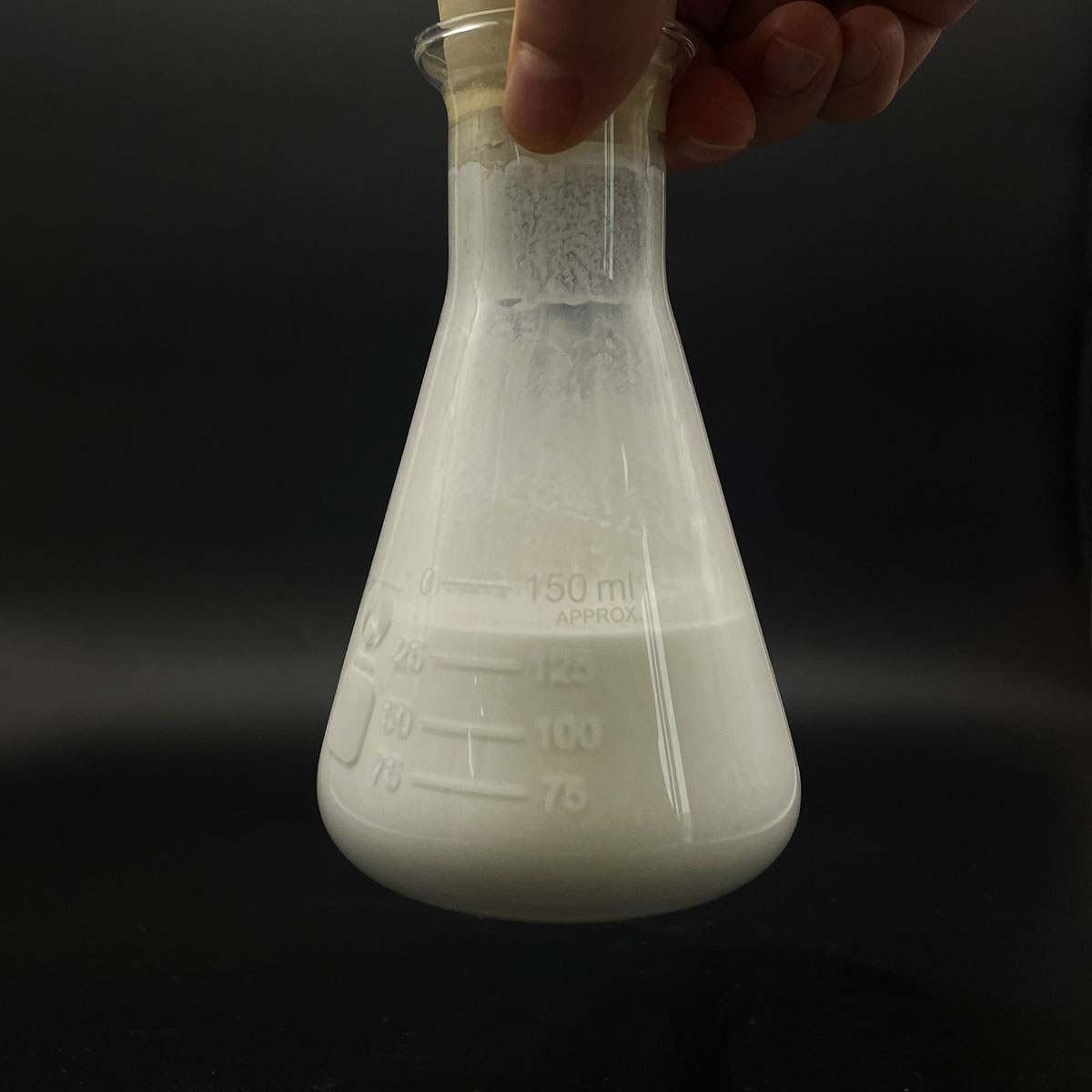

Surfactant is a complex mixture. It’s mostly fats, called lipids, and some special proteins. Think of it like a biological soap. Ever blown soap bubbles? Surfactant works a bit like that soapy film. It coats the inside surface of the alveoli, those tiny air sacs deep in your lungs. The key ingredient in surfactant is a phospholipid named Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC). This is a mouthful, but it’s crucial. DPPC has a unique property. One end loves water (hydrophilic), the other end hates water and loves air (hydrophobic). This dual nature is its superpower. When spread over the wet surface of the alveoli, the water-loving parts sink into the liquid lining. The air-loving parts stick out towards the air space inside the sac. This creates a thin film right at the crucial air-liquid boundary. This film drastically reduces surface tension. Surface tension is the force that makes water form droplets. High surface tension inside the alveoli would be a disaster. It would make the tiny sacs collapse easily. Surfactant stops that collapse. It keeps the alveoli stable and open, ready for the next breath of air. Without it, breathing would be incredibly hard work, maybe even impossible.

2. Why We Need Surfactant

Surface tension is a powerful force. Imagine trying to blow up a brand-new balloon. The first breath is the hardest. You fight against the elastic resistance. Now, imagine billions of microscopic balloons inside your chest. Each one is incredibly small and fragile. The force of surface tension on the liquid lining inside each alveolus is immense relative to its size. High surface tension pulls the walls of the alveoli inward. It wants to shrink the air sac down to the smallest possible size. This is like constantly fighting against collapsing bubbles. During exhalation, as the air sacs get smaller, this collapsing force gets even stronger. Without surfactant, the alveoli would collapse completely at the end of each breath out. Re-opening them for the next breath in would require enormous effort. Your chest muscles would tire quickly. You simply couldn’t breathe efficiently. Surfactant lowers surface tension dramatically. It makes the surface of the alveoli more flexible. It prevents collapse during exhalation. It makes inflation during inhalation much easier. This is essential for efficient gas exchange. Oxygen gets in easily. Carbon dioxide gets out easily. Surfactant makes normal, effortless breathing possible. It saves your body huge amounts of energy every single minute.

3. How Alveolar Cells Make Surfactant

The star players making surfactant are the Type II Alveolar Cells. They are specialized cells nestled among the flatter Type I cells that form the main walls of the alveoli. Type II cells look different. They are cuboidal and often found at the corners where alveoli meet. Their most distinctive feature is visible under a microscope: they are packed with structures called lamellar bodies. These lamellar bodies are like tiny storage warehouses. They hold the pre-made surfactant. Making surfactant is complex cellular work. It starts inside the Type II cell. The cell gathers the raw materials: specific lipids (especially that vital DPPC), cholesterol, and surfactant proteins (SP-A, SP-B, SP-C, SP-D). These components are assembled within the cell’s internal machinery. The endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus are key factories. Here, the lipids and proteins are combined and processed. The final product is packaged into those lamellar bodies. When the lung needs more surfactant, or when the existing layer needs topping up, the Type II cells get the signal. They squeeze the lamellar bodies towards the cell surface. The lamellar bodies fuse with the cell membrane. They squirt their contents – the tightly packed surfactant material – out onto the alveolar surface. This secreted material then unfurls. It spreads out to form the vital surface-active film that coats the alveoli. Type II cells aren’t just factories. They also act as caretakers. They can take up old surfactant components, break them down, and recycle them to make new surfactant. This constant production, secretion, and recycling keeps the surfactant layer fresh and functional.

4. Surfactant Applications in Medicine

Understanding surfactant and its production by Type II cells has revolutionized medicine, especially for newborns. The most critical application is treating Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS) in premature babies. Babies born very early often have underdeveloped lungs. Their Type II alveolar cells haven’t had enough time to mature. They haven’t started producing sufficient surfactant. Without enough surfactant, their tiny alveoli collapse. Breathing becomes a desperate struggle. Before surfactant therapy, RDS was a leading cause of death in premature infants. Doctors now have a powerful weapon. They can give the baby surfactant directly. This surfactant is usually derived from animal lungs (like cows or pigs) or made synthetically. It’s delivered as a liquid through a breathing tube directly into the baby’s lungs. This treatment is often life-saving. It rapidly improves lung function. It makes breathing easier immediately. It allows the baby’s own Type II cells more time to mature and start producing their own surfactant. Surfactant therapy drastically reduced death rates from RDS. Beyond prematurity, surfactant is important in other lung conditions. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) in adults involves damage to the alveoli and Type II cells. Surfactant production or function can be impaired. Research continues into whether surfactant replacement might help some ARDS patients. Surfactant properties are also studied for drug delivery. Scientists explore using synthetic surfactant to help deliver medications deep into the lungs more effectively.

5. Surfactant FAQs

Do Type II cells only make surfactant? No. While surfactant production is their main job, Type II cells have other roles. They act as stem cells in the alveolar epithelium. If the delicate Type I cells lining the alveoli get damaged, Type II cells can divide and transform into new Type I cells to repair the injury. They also help regulate the fluid balance in the alveoli.

What happens if surfactant is missing? As seen in premature babies with RDS, missing surfactant leads to severe breathing difficulties. Alveoli collapse (atelectasis). The lungs become stiff. Inflating them requires high pressure and effort. Oxygen levels drop dangerously low. Without treatment, it can be fatal. In adults, conditions damaging Type II cells or surfactant can cause similar, though often less sudden, problems.

Can we make artificial surfactant? Yes. There are two main types used medically. Animal-derived surfactants are extracted and purified from cow or pig lungs. Synthetic surfactants are made in the lab, replicating the key lipid and protein components. Both types are effective for treating RDS.

How fast do Type II cells replace surfactant? Surfactant turnover is constant and relatively fast. The surfactant layer on the alveoli needs regular replenishment. Type II cells are always working. They secrete new surfactant and take up and recycle old material. This cycle happens continuously throughout life.

(what type of cell produces surfactant)

Why don’t our alveoli collapse when we sleep? Surfactant works 24/7. Its effect on reducing surface tension is constant. Even during sleep, when breathing is slower and shallower, the surfactant layer remains intact. It prevents alveolar collapse at low lung volumes, like at the end of a quiet exhale. This allows easy reinflation with the next breath. Type II cells keep producing surfactant, ensuring the layer stays functional. Our bodies are amazing machines.